What Daisy did next: how Apple’s evolving team of de-manufacturing machines battles e-waste

Apple hopes that e-waste will become a thing of the past thanks to its Daisy family of specialist break-down robots that will transform old iPhones into raw materials

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

First there was Liam, marks 1 and 2. Now there is Daisy, or rather double Daisy, Dave, and Taz. These aren't members of a manufactured pop band but rather Apple's evolving team of advanced de-manufacturing robots.

For the last six years, Apple has been on a mission to develop far more sophisticated and less wasteful machinery and processes for recycling e-waste, specifically that found in redundant iPhones. And that de-manufacturing idea is key.

Apple Daisy and team battle e-waste

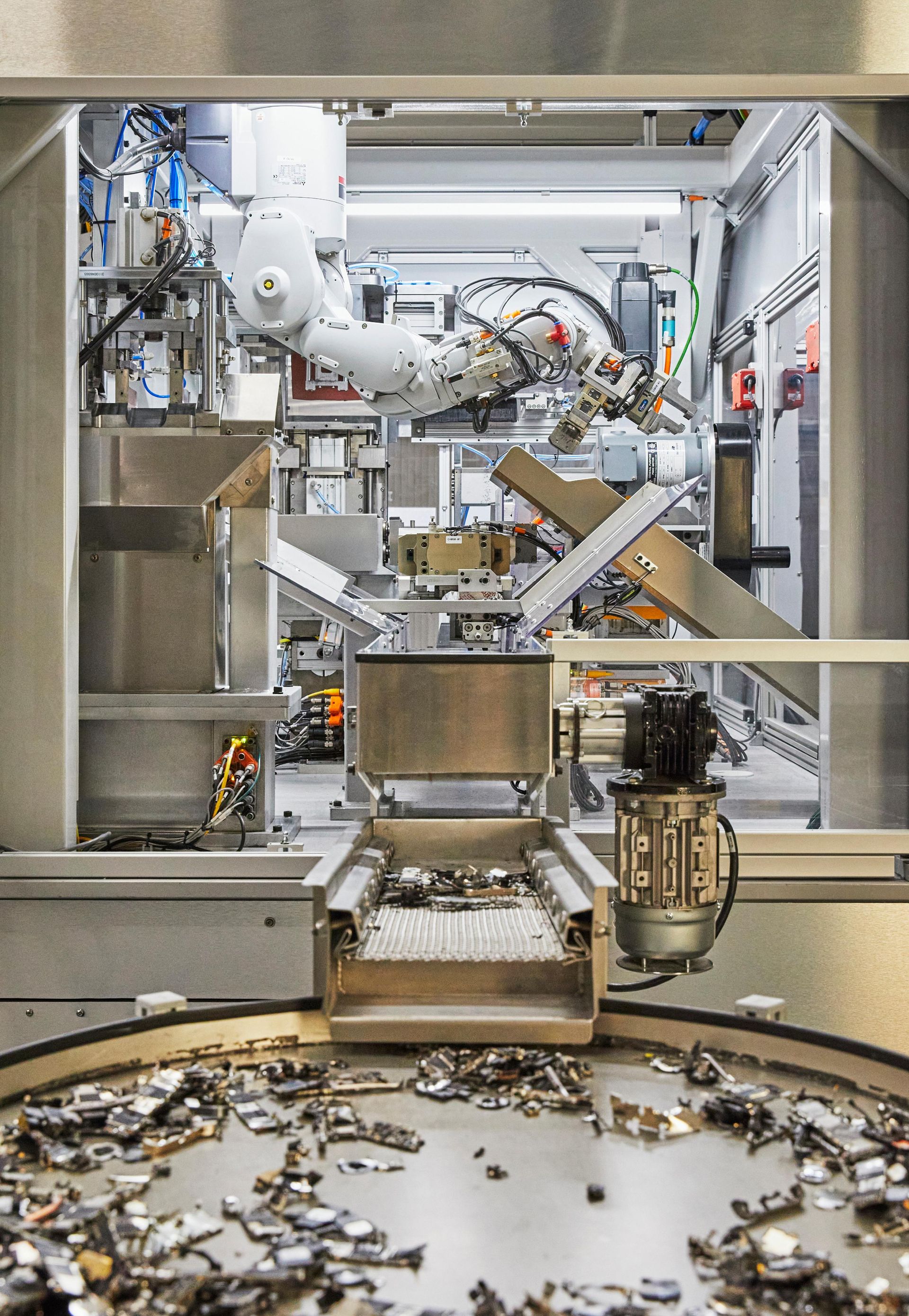

Most e-waste recycling is an exercise in relatively crude crushing and crunching. It renders smartphones – an estimated 12 per cent of all e-waste – and other technology so much fiddly fragments. This makes sorting, separating, retrieving, and recycling precious metals and materials tricky to impossible. Daisy and team have been designed to take apart iPhones with (almost) as much care and attention as they were put together.

As part of its broader material recovery strategy, Apple identified 14 priority materials – from metals including gold and tungsten to paper – that make up 90 per cent of the ingredients used in its devices and packaging, many of which were being recovered in low quantities, in low quality or not at all by existing recycling methods.

An efficient way to pick iPhones apart

The extraction of many of these materials carries a high social as well as environmental cost. Around five per cent of an iPhone’s weight is cobalt. And 60 per cent of the world’s increasingly scarce cobalt is mined, often by hand and in terrible conditions, in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

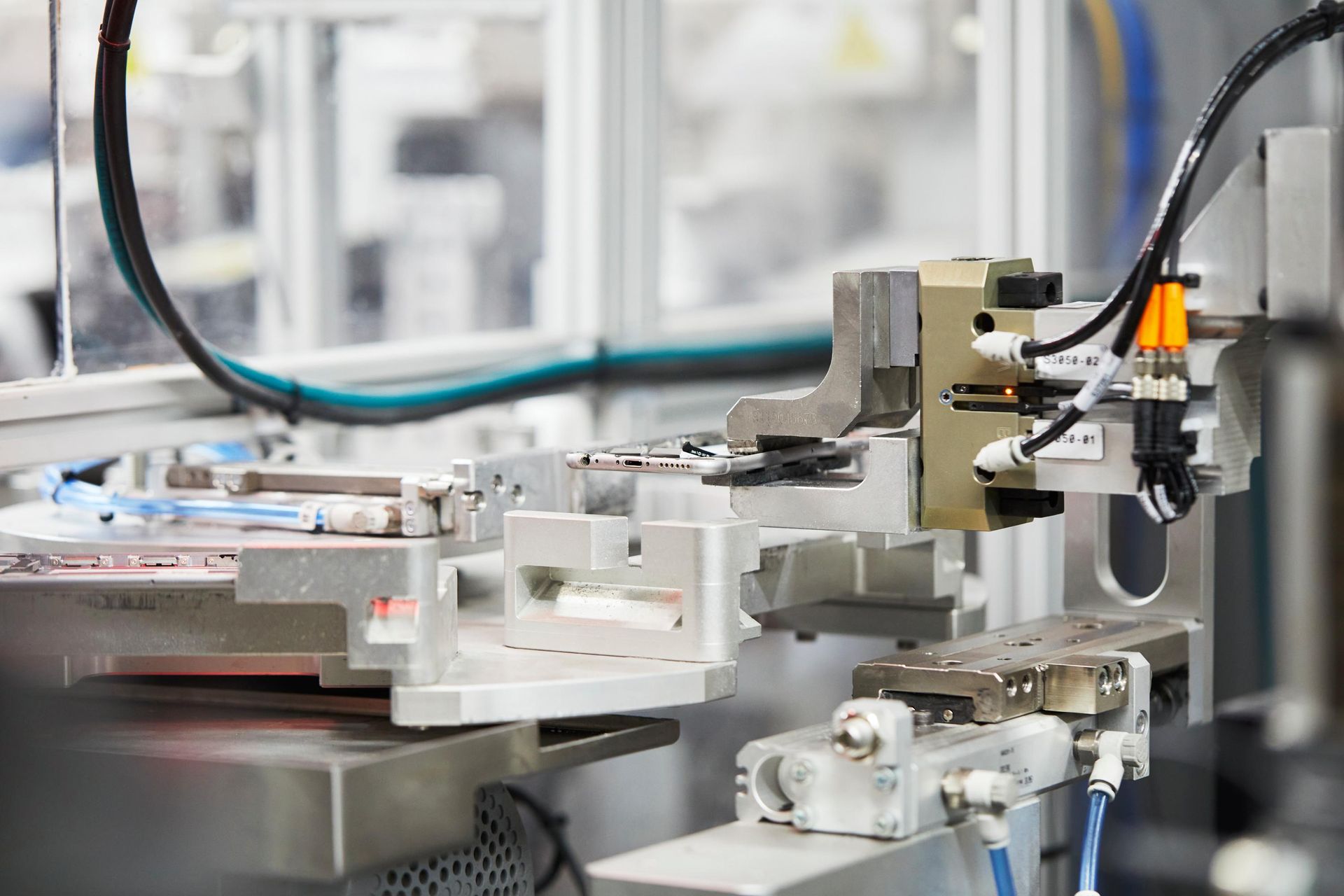

The problem with recovering these materials from a smartphone is that it packs them, in secure and complex ways, in a very small space. An iPhone is more than a powerful computer, chips and circuit boards, it is a camera, music player and more. The camera module alone contains tin, copper, gold and other rare earth materials. There are also lenses and tiny speakers to retrieve and disassemble. Apple needed to find an efficient way to pick iPhones apart.

Set up in 2016, Liam was Apple’s first stab at a robot-manned de-manufacturing line. It could only handle iPhone 5s and it took 12 minutes to dissemble each one. This was unfeasibly slow but worked as a proof of concept. Liam 2.0 was a full 30m long, employing a row of 29 separate robots. It sped up the de-production process, but one fundamental time-sucking problem was holding it back. Robots make slow work of unscrewing tiny screws. Liam was replaced by Daisy in 2018 and it abandoned delicacy and applied brute force, simply punching a hole around screws. This was the key feasibility unlock.

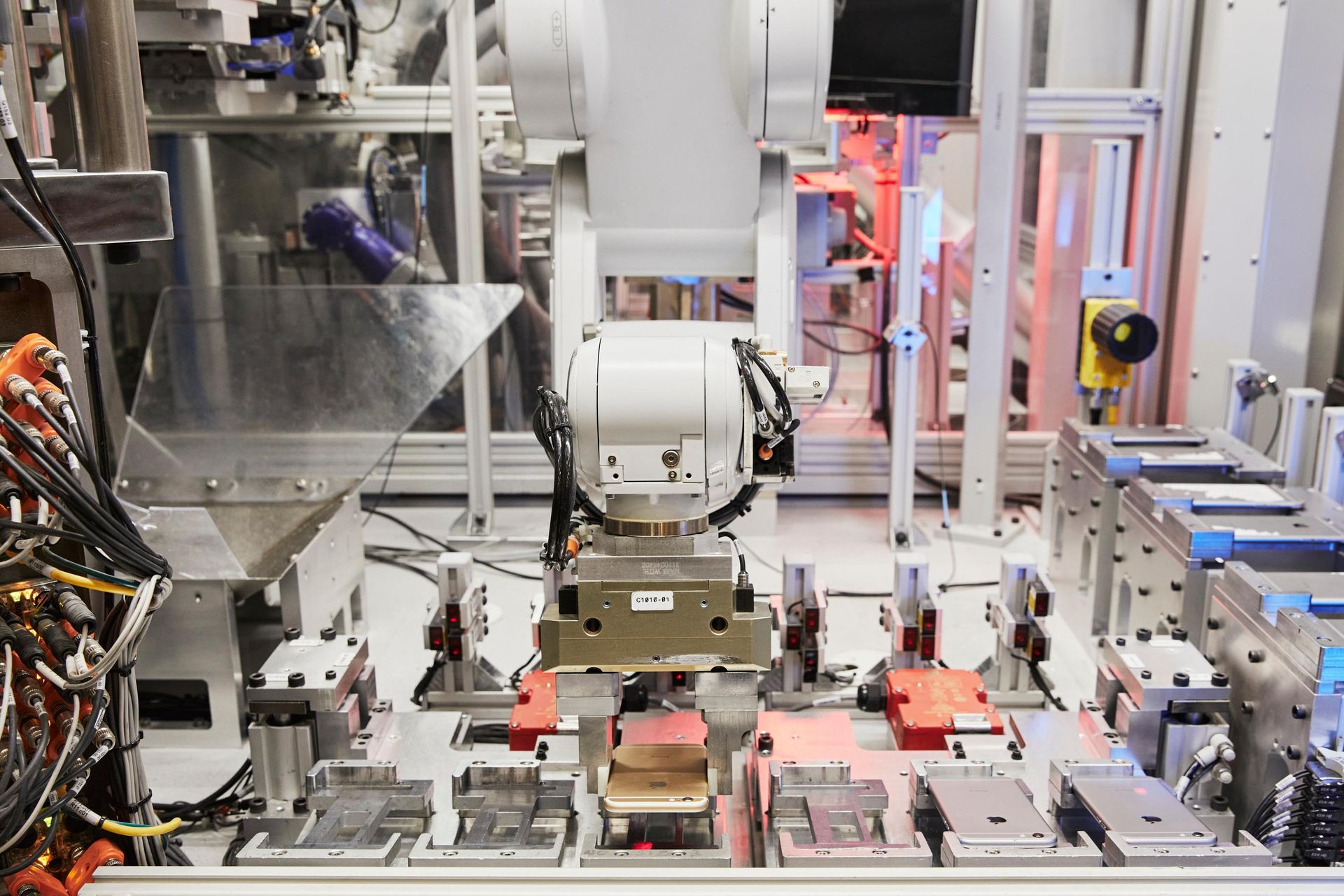

A 10m-long, five-robot reverse production line, Daisy is made up of four cells that break down an iPhone into 15 component parts. Cell one opens up the phone, another uses minus-80-degree Celsius cold air to nullify the adhesive that attaches the battery to the housing, another punches out screws, while the final cell separates components from the housing. Armed with sophisticated AI, Daisy can now identify 23 different models of iPhone and process one every 18 seconds, in whatever order they come.

Robot Dave, meanwhile, tackles the iPhone's 'Taptic Engine' to recover tungsten, copper and gold and its steel enclosure. Taz then separates magnets from plastics in speakers. Humans appear at the end of the chain to manually sort and separate materials.

Towards circularity

That might seem like a lot of effort but – given the colossal wastefulness of extraction – Daisy and co have an outsize impact. One metric ton of recovered iPhone parts avoids the mining of 2,000 metric tons of metal-rich rock.

Daisy is sold as a key part of Apple’s progress towards full circularity. It hasn’t put a timescale on achieving that goal and many commentators argue that, given the complexities of Apple’s resource-hungry products and its supply chain, it’s an all-but-impossible dream. Apple, though, has made advances. It has been using recycled tungsten since iPhone 12 and 100 per cent recycled certified gold since iPhone 13. In the financial year 2021, 20 per cent of material Apple shipped came from recycled sources and the 13-inch MacBook Air has 40 per cent recycled content. It has also been investing in establishing industry-wide bona fides for recycled material.

The problem for Apple, leaving it open to accusations that Daisy is more PR stunt than practical solution, is the limited supply of old, unrepairable or un-resalable devices. There’s currently one Daisy in the Netherlands to handle permanently retired European iPhones and another in Texas at Apple's Material Recovery Lab, helping take care of US business. A single Daisy could disassemble up to 1.2 million iPhones every year and Apple is keen to have four of five Daisies up and running as soon as possible. At the moment, though, neither Daisy is working at anywhere near full capacity.

Too many of us stash our old phones away in drawers or use third-party trade-in services. The battle now is to incentivise people to return phones to Apple so they can be refurbed – in the 2021 fiscal year, Apple sent 12.2 million refurbed devices to good new homes – or fed to Daisy. Apple does now have its own trade-in service, which can be used to offset the cost of an upgrade. And in the 2021 financial year that helped push 38,000 metric tonnes of e-waste to recycling.

While notorious for its privacy around product development, Apple is open-sourcing the tricks and technology behind its materials recovery programme, hoping that other tech companies and recycling specialists will adopt, adapt and perhaps even advance those processes. Critics argue that Daisy clones are too expensive an option for third-party recyclers and none have, as yet, taken up the option to create one.

iPhone 12: ready for recycling?

On a more positive note, and despite the yearly roll-out of faster, smarter best-ever devices, more and more of us are holding on to our phones for longer. Upgrades now feel more like marginal gains than absolute musts. And Apple insists that durability and longevity of devices is now a priority. It has also gone some way to answering the demands of the ‘right to repair’ movement. Last year it made spare parts and repair manuals for the iPhone 12 and 13 available in the US. That will soon be extended to the iPhone 14 and some MacBooks and made available in Europe.

Of course, Apple is still very much in the business of selling new iPhones. It is estimated that 240m were sold in 2021, despite the pandemic, and iPhone sales account for over half of Apple’s revenue. Efficiently dealing with smartphone e-waste is only going to become more of a problem. It is, though, also big, profitable business – if done properly – and recycling specialists are making advances. Daisy isn’t the only show in town. But while a Daisy army might not be the sole solution to putting smartphone parts back into circulation, they are the smartest, sharpest tool available.

Apple.com (opens in new tab)

-

Watch Ryuichi Sakamoto's mesmerising musical experience at the Brooklyn Museum

Watch Ryuichi Sakamoto's mesmerising musical experience at the Brooklyn MuseumAn iconic composer who traverses popular and high culture, Ryuichi Sakamoto pushes music into new frontiers, most recently in ‘Seeing Sound, Hearing Krug’, a new composition that pairs sound, flavour, light and texture

By David Graver • Published

-

Last chance to see: ‘Strange Clay’ at The Hayward Gallery, London

Last chance to see: ‘Strange Clay’ at The Hayward Gallery, LondonAt London’s Hayward Gallery, group show ‘Strange Clay: Ceramics in Contemporary Art’ sees ceramic artists explore the physical, psychological, political and power of their medium

By Emily Steer • Published

-

Aehra is Italy’s first all-electric luxury car brand. We preview its forthcoming SUV

Aehra is Italy’s first all-electric luxury car brand. We preview its forthcoming SUVAehra’s proposed electric SUV is brimming with cutting-edge technology. The Italian company hopes to shake up the high-end EV market in 2025

By Jonathan Bell • Published