Regenerative design: meet the creatives taking a rooting interest in learning from nature

Regenerative design: meet the creatives taking a rooting interest in learning from nature

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- (opens in new tab)

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Are you sitting comfortably right now? In this age of eco-anxiety, imagine how at ease you would feel to know that the sofa you are reclining on isn’t just made from renewable or recycled materials, but produced in a way that encourages biodiversity to thrive. Or that the home you are living in is designed to help other species to flourish.

Regenerative design: doing less harm is not enough

DnA_Design and Architecture has converted local stone quarries into cultural spaces

It seems a radical idea, but as the climate crisis deepens, ‘sustainable design’ and ‘doing less harm’ are not enough to avert catastrophe – we have to find ways to replenish ecosystems while meeting our own needs. ‘Humans need to return to a state where they are co-evolving with nature,’ says architect and biomimicry expert Michael Pawlyn. ‘If we carry on believing that it is something to be plundered for resources, it will be our undoing.’

Pawlyn is one of the architects leading the charge for a shift towards ‘regenerative design’, which ‘supports the flourishing of all life, for all time,’ as he puts it in his new book Flourish: Design Paradigms for Our Planetary Emergency, co-written by Sarah Ichioka. While sustainable design focuses on mitigating problems, regenerative design is about restoring the damage wreaked by human hands, nurturing biodiversity and taking carbon out of the atmosphere while we produce homes, infrastructure, furniture and food. ‘We’ve got to get to a point where we integrate all our activities into the web of life that surrounds us, overcoming our separation from nature,’ adds Pawlyn.

The architect sees biomimicry – the design of materials or structures modelled on biological systems – as one way forward. ‘We can learn from nature, looking at how it stewards things in closed-loop cycles,’ he says. His practice, Exploration Architecture, co-initiated the Sahara Forest Project Foundation, an environmental platform that aims to revegetate low-lying desert areas and grow food. The 2012 pilot plant in Qatar incorporated a greenhouse inspired by the Namibian fog-basking beetle’s method of harvesting fresh water in the desert, quickly returning biodiversity to this arid region.

A further pilot launched in Jordan in 2017. Models of some of his more recent designs – including the Biomimetic Office, a speculative design that took cues from a spook fish, and a table inspired by tree and bone growth – are now on show in Granada, Spain, as part of the travelling exhibition ‘BioInspiration: Innovating from Nature’.

Regenerative design from indigenous communities

Pawlyn points out Indigenous communities around the world have been designing regeneratively for centuries. The Khasi community of Meghalaya, India, for example, create bridges by training the aerial roots of rubber fig trees to grow across rivers. If they were to cut them down and use the timber, the wood would rot in the monsoon rains, releasing carbon back into the atmosphere. Instead the living root bridges grow stronger over time, supporting the life around them.

Indigenous design concepts have often been dismissed due to cultural biases, but designers around the world are beginning to recognise the importance of traditional ecological wisdom. Engineering firm Buro Happold and designer Julia Watson have collaborated with members of the Khasi community for an exhibition at London’s Barbican. Their architectural model imagines how nature-based infrastructure could be integrated into cities, showing a canopy of trees running through an urban centre. It would provide shade, minimise urban heat effect, and become more load-bearing over time to accommodate foot traffic and infrastructure, such as bus shelters.

Working in partnership with nature: the creatives leading the way

DnA_Design and Architecture’s 2015 Bamboo Theatre in China’s Zhejiang province was built in less than two weeks

‘A huge amount of what we learned also goes beyond what a model can convey,’ says Smith Mordak, director of sustainability and physics at Buro Happold. ‘We learned that we need to work in partnership with nature, not force it, and establish a deeper sense of time, both for architectural interventions and to allow the passing of knowledge down the generations. It’s imperative we recognise that those of us in the Western design community are not the experts. We have much to learn.’

The notion of working with living plants is taking root elsewhere in the world. In China, DnA_Design and Architecture wove bamboo into a vault formation to create the Bamboo Theatre in 2015. ‘It’s my favourite project because it was so easy and quick to do,’ says founding principal Xu Tiantian. It was designed in one afternoon and constructed in less than two weeks, with the bamboo’s root system acting as the theatre’s foundations.

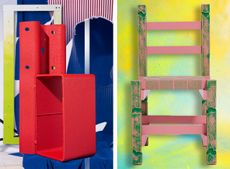

Xu believes that today’s narrow definitions of architecture are limiting its ability to respond to nature’s needs. ‘Architecture has become like product design, with technology being the main content and traditional wisdom being ignored,’ she says. The theatre is part of DnA’s ‘architectural acupuncture’ strategy in Songyang County, which aims to re-instil ‘rural self-confidence’ through minimal interventions with big impact. Recent projects include the conversion of abandoned stone quarries into cultural spaces using ‘micro renovations’. ‘We wanted to restore the ecology of the sites and add a few layers of our own,’ Xu explains. ‘Architecture doesn’t have to be about new buildings, it can be about creating spaces in nature to accommodate functions and programmes.’

The Hempstack pavilion, built in hempcrete in 2021 in the garden of Guan Lee’s laboratory at Grymsdyke Farm, Buckinghamshire. Project team: Hyelyn Lee, Danae Mavridi, Nora Brudevold and Matteen Haj Seyed Javadi, taught by Daniel Widrig, Guan Lee and Adam Holloway, Material Architecture Lab, MArch. Architectural Design, The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

Another way to design regeneratively is to grow or make materials from atmospheric carbon, such as wood, hemp, willow and straw. Hemp can sequester carbon twice as effectively as forests, according to Cambridge University researcher Darshil Shah, and can be grown in many parts of the world, with a positive impact on soil quality. This is prompting designers to experiment with it.

Typically made from water, hemp shives and lime, hempcrete is used largely as infill for timber-framed walls at present. Architect Guan Lee and the Material Architecture Lab at the Bartlett School of Architecture have been testing its tensile strength and durability at Lee’s laboratory in Buckinghamshire. Using hempcrete, wire mesh and gravel, they created the Hempstack pavilion in 2021, and are now watching how it responds to Britain’s weather conditions. ‘Hempcrete is certified as something that needs to be protected from the elements, so we want to figure out how long it takes to deteriorate to determine future uses,’ says Lee. ‘So far, so good.’

The cement industry alone generates 2.8bn tonnes of CO2 every year, so replacing concrete with a carbon negative alternative could be meaningful. But ‘to be truly regenerative, biocomposites must be made using a natural resin,’ explains Pawlyn. That’s if resins are necessary at all. He sees regenerative promise in those of London company Biohm, founded by designer Ehab Sayed. Biohm creates insulation panels by feeding mycelium with waste materials from agriculture and construction. The company says its entire manufacturing process has a positive impact on the planet, sequestering at least 16 tonnes of carbon dioxide a month.

Fernando Laposse’s ‘Agave’ armchair, 2021, made with sisal, a natural fibre harvested from agave, as part as a project to restore soil quality

Modern agriculture also has much to answer for: about half of the world’s habitable land has been colonised to produce food and materials, displacing Indigenous people and forcing what little biodiversity is left to exist on scraps of land. But designers are beginning to promote more regenerative agricultural practices. In Finland, Italian studio Formafantasma is helping furniture company Artek deduce how it can influence the way forests are managed to encourage greater biodiversity. Meanwhile, in Mexico, Fernando Laposse is working with locals in the rural community of Tonahuixtla to restore the soil quality of land desertified by chemical-heavy industrial farming (see W*256). They have planted agaves over 120 hectares, using an Indigenous terracing system to improve water retention. Laposse extracts the sisal, a natural fibre harvested from agave, to make his shaggy seating collections, which in turn finance further environmental repair.

Such ideas suggest nature and humans can thrive together if we learn from traditional wisdom and nature’s own ingenuity, and consider the needs of all species in the design process. Our conscience could rest more comfortably if the objects around us helped with more than just our own wellbeing. Laposse’s hairy sisal sofas, for example, offer a warm embrace for both body and soul.

INFORMATION

‘BioInspiration: Innovating from Nature’ is at Granada’s Parque de Las Ciencias until 31 August 2022

parqueciencias.com (opens in new tab)

‘Our Time on Earth’ is at London’s Barbican until 29 August 2022

barbican.org.uk (opens in new tab)

-

Men’s engagement rings for modern grooms

Men’s engagement rings for modern groomsMen’s engagement rings, whether classic or colourful, make for sentimental tokens

By Hannah Silver • Published

-

Longchamp unites with D’heygere on a playful collection made to ‘transform the everyday’

Longchamp unites with D’heygere on a playful collection made to ‘transform the everyday’Inspired by Longchamp’s foldaway ‘Le Pliage’ bag, this collaboration with Paris-based jewellery and accessories designer Stéphanie D’heygere sees pieces that ‘transform and adapt’ to their wearer

By Jack Moss • Published

-

Last chance to see: Marc Newson’s all-blue designs in Athens

Last chance to see: Marc Newson’s all-blue designs in AthensGagosian gallery Athens presents new blue furniture and objects by Marc Newson

By Rosa Bertoli • Published

-

Shellmet: the helmet made from waste scallop shells

Shellmet: the helmet made from waste scallop shellsShellmet is a new helmet design by TBWA\Hakuhodo’s creative team and Osaka-based Koushi Chemical Industry Co, made using Hokkaido’s discarded scallop shells

By Jens H Jensen • Published

-

Wentz presents innovative furniture incorporating ocean plastic waste

Wentz presents innovative furniture incorporating ocean plastic wasteThe ‘Mar’ collection by Guilherme Wentz is informed by the sea and features computerised 3D-weaving techniques to transform ocean-borne plastic

By Scott Mitchem • Published

-

Liaigre ‘Upcrafted’ objects showcase potential of sustainable design

Liaigre ‘Upcrafted’ objects showcase potential of sustainable designStriding confidently towards more sustainable production, interior design company Liaigre has released ‘Upcrafted’, a series of limited-edition objects for the home, assembled attentively from the studio’s would-be waste

By Martha Elliott • Last updated

-

No time for waste: Oris’ collaboration with a leather manufacturer recycles deer skins

No time for waste: Oris’ collaboration with a leather manufacturer recycles deer skinsDeer skins make for sustainable watch straps in a partnership between Oris and Cervo Volante

By Hannah Silver • Last updated

-

Cooking Sections champions regenerative eating at the Serpentine’s The Magazine restaurant

Cooking Sections champions regenerative eating at the Serpentine’s The Magazine restaurantLondon-based artist duo Cooking Sections has created a menu of three dishes for The Magazine restaurant at Serpentine North, as part of the museum’s ‘Back to Earth’ programme featuring artistic responses to the climate emergency

By Sheila Lam • Last updated

-

Best recycled designs from the Wallpaper* Design Awards

Best recycled designs from the Wallpaper* Design AwardsContemporary designers are using waste to create furniture designs that combine a distinctive aesthetic with a sustainable approach

By Anne Soward • Last updated

-

Terra Carta Design Lab announces finalists

Terra Carta Design Lab announces finalistsHRH Prince Charles and Jony Ive, in collaboration with the Royal College of Art, announce the 20 finalists of the Terra Carta Design Lab

By Rosa Bertoli • Last updated

-

Jony Ive’s LoveFrom unveils Terra Carta Seal design

Jony Ive’s LoveFrom unveils Terra Carta Seal designDesigned by Jony Ive to celebrate nature, with an intricate composition of flora and fauna, the Terra Carta Seal represents the charter’s values and will be bestowed upon private sector companies that distinguish themselves for their sustainability efforts

By Sarah Douglas • Last updated